Celebrating 10 Years of Tribe’s Cleanup Partnership at Tar Creek Superfund Site

– EPA Region 7 Feature –

By Madelyn Bremer, Public Affairs

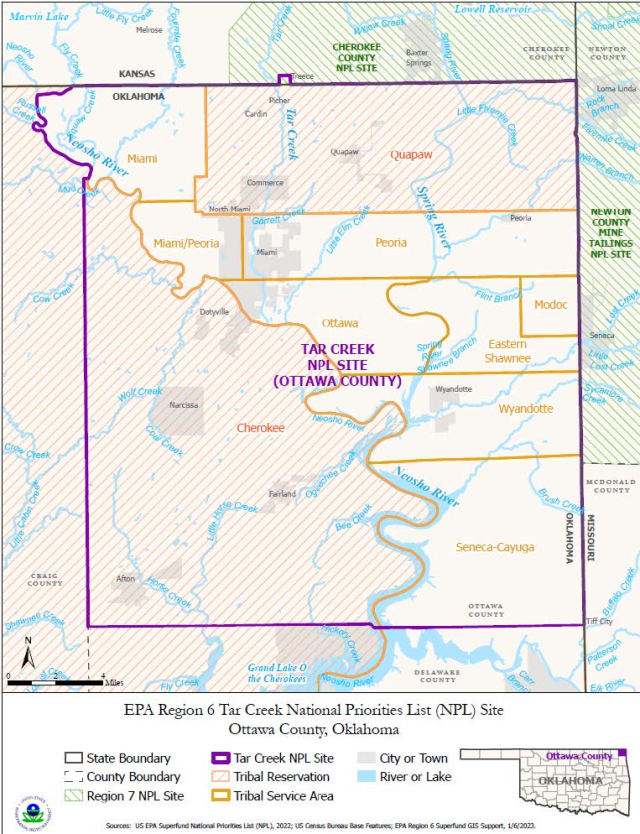

On a warm autumn day, EPA officials gathered in Quapaw, Oklahoma, joining the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality and members of the Quapaw Nation to celebrate a decade of partnership and progress at the Tar Creek Superfund Site (see site map at right).

October 2023 marked 10 years since the Quapaw Nation took over cleanup efforts at the culturally and historically important Catholic 40 site, making the Tribe the first in the nation to lead remedial operations at a property on a Superfund site.

Historic Mining Leads to Environmental Concerns

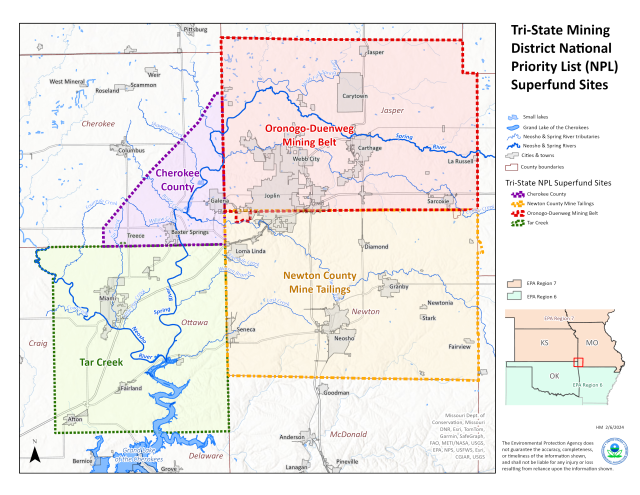

The community of Quapaw is located in the middle of the Tri-State Mining District (TSMD), one of the nation’s largest historic mining areas. The TSMD encompasses areas of northeastern Oklahoma, southeastern Kansas, and southwestern Missouri, where lead and zinc mining flourished in the early 20th century.

Metal ores were first discovered in northeastern Oklahoma in the late 1800s, but mining in the area boomed after a major ore discovery near what became Picher, Oklahoma.

“Picher Field,” covering areas of Oklahoma and Kansas, was mined for over 70 years. Excavations from the area were primarily used to make ammunition. Over 75% of American bullets and shells used in both World Wars could be traced back to the TSMD. In fact, at one time, nearly 55% of the world’s heavy metals came from the area.

However, profits declined with the depletion of ores in the 1960s and the mines were completely abandoned by 1974.

Throughout seven decades of operation, over 300 mines and hundreds of exploratory boreholes were drilled into the landscape – all of which were left unsealed when mining ceased. Water had been pumped out of the shafts when mines were active, but those pumps were disabled with the abandonment of the mines. Not long after mining stalled, the open holes began to fill with water and brought heavy-metal contamination to the surface.

Widespread Contamination

Tar Creek is an 11-mile-long waterway beginning in Kansas and flowing south through several communities in northern Oklahoma. In 1979, the creek turned bright orange. What had once been a water source and gathering place for the community quickly became the first sign of serious environmental issues.

Acidic water flowing from the mineshafts dumped toxic elements like lead, zinc, arsenic, and cadmium into the creek, killing plant and animal life downriver and sickening the community. The brownish-orange creek, caused by rusting iron in the water, stained everything in its path. This small, 11-mile-long waterway was soon regarded as one of the worst environmental disasters in the nation.

Aside from contaminated water, the TSMD is plagued by piles of “chat,” the local name for mine tailings containing toxic lead dust. Chat is rampant in the area – for every ton of ore extracted at the site, over 16 tons of chat were left behind.

Today, the area has approximately 30 million tons of chat, with some mounds towering to nearly 200 feet. When the wind blows, it carries contaminated dust from the piles with it, and when it rains, contaminated water will pour out of the chat for weeks on end.

Contamination Concern Draws EPA's Attention

EPA began observing Tar Creek in 1979 when the creek first changed color and officially designated it a Superfund site with National Priorities List (NPL) placement in 1983.

EPA began to address surface water and soil contamination by filling abandoned wells and conducting soil tests in residential and high-access areas, like day cares and schools. In the late 1990s, concerns that contamination on residential properties was worse than previously thought inspired the federal government to instate a federal buyout program for impacted homes. By 2010, the four local communities of Picher, Cardin, and Douthat, Oklahoma; and Treece, Kansas, had unincorporated and all but been abandoned.

Today, the TSMD is divided into four Superfund sites on the NPL: Cherokee County Site (Cherokee County, Kansas); Newton County Mine Tailings Site (Newton County, Missouri); Oronogo-Duenweg Mining Belt Site (Jasper County, Missouri); and Tar Creek Site (Ottawa County, Oklahoma). See map at right.

The Tar Creek Superfund Site remains one of the nation’s largest Superfund sites, spreading over 40 square miles and 25,699 acres of land across Oklahoma.

Quapaw Nation Impacts

The Quapaw Nation of northeastern Oklahoma has lived in the area since 1834, long before lead was first discovered and mining operations began. To this day, most citizens reside within 30 miles of the Tribal Headquarters in Quapaw. Due to its proximity to the Tar Creek Superfund Site, members of the Quapaw Nation have been historically and disproportionately impacted by Tar Creek’s contaminated waters.

In 1994, test results from the Indian Health Service showed that 35% of Native American children in the area had concerningly high blood lead levels. Another area study that examined young school children showed that they had over 43% elevated blood lead levels – 11 times the state average. Concerns about these results prompted the Quapaw Nation to seek immediate assistance from EPA and other federal agencies.

Through the EPA Region 6 General Assistance Program, the Quapaw Nation Environmental Office was established in 1997. The following year, the Quapaw Tribal Chair and EPA Region 6 Administrator signed a Tribal Environmental Agreement, which served as a formal partnership to address issues regarding the environmental protection of Quapaw lands. The Quapaw Nation worked with EPA Regions 6 and 7 for over 15 years to develop the Tribe’s technical ability to administer environmental responses.

In 2013, the Quapaw Nation negotiated with EPA to self-remediate a 40-acre parcel within the Tar Creek Superfund Site, because of its sensitive nature to the Tribe. This site, known as the “Catholic 40,” is an area with significant cultural history for the Quapaw Nation, and the Tribe hoped to preserve the historical landmarks within the site to better understand their past.

“The Catholic 40 is the site of a former school, St. Mary’s of the Quapaw, where Quapaw children were educated. When the school closed in the 1920s, the site was leased for mining, then returned to the Nation contaminated by thousands of tons of mine waste,” said Summer King, an environmental scientist with the Quapaw Nation Environmental Office. “When the site was slated for remediation, the Quapaw Nation requested to conduct the work. Because of the cultural and historical importance to the Nation, they knew their own people were the best for the job.”

In less than a year of cleanup efforts (and ahead of schedule), the Quapaw Nation excavated, hauled, and disposed of over 107,000 tons of chat within the Catholic 40. Over the past 10 years, the Tribe has contracted with EPA and the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality to oversee remedial operations at this site.

During that decade, the Quapaw Nation worked with engineering firms and other local, state, and federal partners to remediate the Catholic 40 and adjacent lots of the Tar Creek Site on both sides of the Kansas-Oklahoma border. Quapaw environmental remediation specialists have removed millions of tons of chat, introduced soil amendments to decontaminate the land, and reintroduced native plants to cover the area, returning previously unusable land back to productive use.

“The Quapaw Nation Environmental Office (QNEO) has overseen the removal of more than 7 million tons of mine waste from Tar Creek and remediated more than 600 acres of land. Our construction department has doubled in size, and the Nation has invested in new and upgraded equipment,” King said. “On the technical side, QNEO environmental scientists have learned about soil amendments that bind metals in-situ and reduce the amount of waste that needs to be removed from a site. They have designed and overseen construction of wetlands and planted thousands of native plants and seeds.”

Looking Forward to Remediation

Throughout Tar Creek's history, EPA has engaged in partnerships across regions, states of Oklahoma and Kansas, Quapaw Nation, and numerous other stakeholders. These partners continue to work together to find solutions and make headway in the remediation efforts of one of the nation’s largest Superfund sites, just as it has for nearly 40 years.

Although the Catholic 40 represents only a portion of the entire Tar Creek Superfund Site, the site serves as an example of what proactive partnerships can achieve. EPA’s relationship with the Quapaw Nation shows what solutions can be found when agencies partner with the communities impacted most.

“Working in the Superfund field can be backbreaking and heart-wrenching. But seeing a site change from actively hazardous to a beautiful green pasture is all the reward needed. I won’t live to see this site completely clean, but I can train the next generation who may be lucky enough to see that day,” King said.