Fifty Years of Protecting the Ocean

In October 2022, EPA celebrated the 50th anniversary of two significant environmental laws that protect oceans, bays and estuaries in the U.S. The Clean Water Act is more commonly known, but the lesser-known Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act is also of great importance. Passed in 1972, this act prohibits the dumping of certain types of waste into the ocean and established one of the first international agreements to protect marine environments from human activities. It guides the work of EPA Pacific Southwest oceanographer Allan Ota whose passion for the ocean began when he was a child. “I grew up watching Jacques Cousteau exploring the sea on TV. It captivated me,” Ota states.

EPA Oceanographer Allan Ota and Team Protect Coastal Resources

Ota and his Ocean Dumping-Sediment Management Program team oversee and monitor the disposal of non-toxic sediments at 12 designated sites offshore in California, Hawaii and Guam. Dredging harbors and shipping channels supports safe navigation and benefits the economy. Commercial ports in the Pacific Southwest, for instance, account for 30% of the U.S. maritime economy. Sediments build up in urban estuaries where ports, marinas and channels are located. The team may approve the disposal of clean sediments in the ocean, but contaminated materials must go to an appropriate disposal facility or an upland site. The sediment program’s aim is to ensure shipping vessels can safely move in and out of ports, while protecting the marine environment.

Promoting Safe Navigation While Protecting Wildlife

Dredging in harbors and estuaries can affect wildlife. Fish, sea turtles and other wildlife use these areas as seasonal migratory corridors. Harbors and estuaries support eel grass beds and other habitats that provide nurseries for juvenile fish. Dredging near sensitive habitats requires that EPA collaborate and consult with the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Together they assess projects that range from how dredging affects sea turtles and other sensitive species to how using sandy sediments to restore beaches impacts nesting birds. The team also works with state agencies to ensure all proposed dredging projects include testing of sediments for pollutants to protect water quality.

When dredging, the team uses silk curtains in the water to contain sediments and reduce turbidity, which helps protect sensitive marine habitats. Once excavated, the dredge bucket drops sediments into a screen on the barge, which separates larger materials from finer mud and sand. Ota notes “often trash, even things like refrigerators, are sadly a common occurrence in urban estuaries and harbors. Removing this trash helps keep the marine environment cleaner.” Ensuring Dredged Sediments are Clean and Safe

Ota and the team test dredged sediments for different types and levels of chemicals to ensure they’re safe and clean. These tests help determine if sediments are suitable for disposal in the ocean, on land, or for restoration projects. The team evaluates health risks from exposure to these chemicals over the short- and long-term. Dioxin, in particular, Ota states, is a chemical of concern, because it is widespread, highly toxic, and takes a long time to break down in the environment.

Monitoring Sediment Deposits and Protecting Marine Sanctuaries

Non-toxic sediments are eligible for disposal at a designated ocean site. Using computer models, the team identifies offshore locations where deposited sediments will not widely disperse and adversely affect the surrounding marine environment. EPA also conducts an environmental evaluation for of each site under the National Environmental Policy Act. Every 10 years, the team updates site management and monitoring plans. This oversight is essential for protecting sensitive areas like national marine sanctuaries offshore of San Francisco, including Gulf of the Farallones, Monterey Bay and Cordell Bank. Ota adds, “I’m especially proud that in my 30 years of monitoring our ocean disposal sites, our team has always been able to identify the dredged sediment deposits and confirm they aren’t toxic. It shows the program is working.”

Digital Cameras are a Game Changer for Testing Sediments

“Advanced underwater cameras are a game changer for the sediment-testing program,” Ota states. He remembers when underwater cameras were film-based. Because the deep sea is very cold, the entire camera housing was near freezing when brought on board. The team had to slowly heat it up to room temperature before opening the housing to prevent condensation and conductivity problems with the inner circuit boards, batteries and cameras. They then had to follow several steps using lightproof canisters and bags because there was no darkroom on the ship.

One Misstep Could Ruin the Film

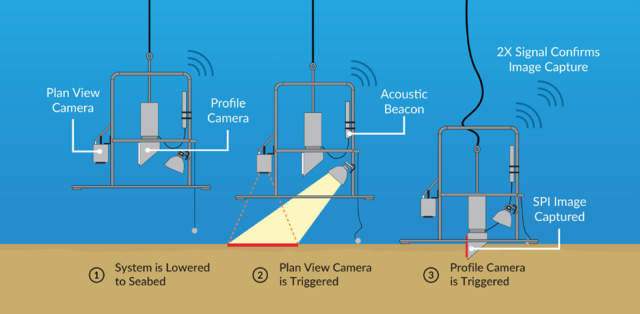

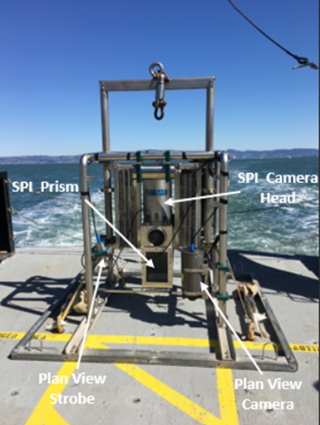

Today, digital cameras holding thousands of high-resolution images allow sampling at more sites. Hydraulic pistons slowly lower the attached camera frame into the seafloor to record images of different layers of sediments. With a resolution of millimeters, this advanced camera system can map the edge and thickness of the dredged material deposit. This allows the field team to determine how far the footprint of the dumped sediment has spread.

Restoring Wetlands and Beaches Benefits Communities

Ota is excited about efforts to reuse clean sediment to restore and maintain wetlands and replenish beaches. Sea level rise driven by climate change is inundating wetlands with sea water and eroding beaches. As coastlines recede and beaches become narrower or even disappear, local communities are vulnerable to flooding and other severe weather events. These events can destroy property, infrastructure and even result in deaths. Reusing sandy sediments to replenish and maintain beaches helps protect communities and provides a place of natural beauty to recreate.

Like beaches, maintained and restored wetlands act as buffers during storms. Sea level rise affects wetland plants, which require optimal water depths to survive and grow. Depositing the right kind of sediments in these natural areas can help plants maintain their ideal depth. Restoring wetlands is particularly vital in California’s San Francisco and San Diego bays, which have lost 90 percent of their historic wetlands.

Wetlands that have been restored help protect shorelines and reduce the impacts of sea level rise. Federal, state and local agencies are working with communities to fund wetland restoration projects, which will have long-lasting benefits.

Ota is proud to serve on this EPA team that works to protect the marine environment, coastal wetlands and communities. He hopes that as people experience wetlands, they will understand how coastal environments promote climate resilience and feel inspired to protect them.