Why Stories Matter

I find it enchanting how storytelling is both universal and subjective. Childhood houses, the cultures of our parents, and languages spoken at home, can make a profound impact on how stories are told. I have lived a nomadic life across several cultures throughout the world, paving my path to ultimately serve as a speechwriter for the EPA.

It was this unconventional life cradled by the misgivings of an identity crisis that propelled me into the world of writing and storytelling. I believe engaging the public through sharing EPA stories is some of our most important work, and I’ve discovered that hearing stories from all corners of the globe inadvertently prepared me for this role.

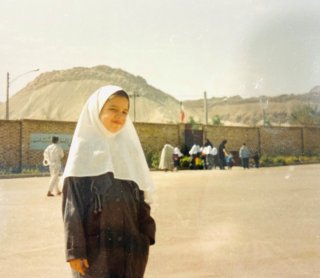

My mother, an American from North Carolina, and my father, an Arab from Iraq, crossed paths in a culture clash of paradoxes, bringing into the world bi-cultural children. When I was four years old, my family moved to Iran during a reprieve following a decade of violence and war. Our home was surrounded by books written by my father in Arabic, his evenings spent writing longhand under a dim light while smoking a pipe. We lived in Iran because it bordered Iraq, my father’s home country. But as I observed him writing book after book on theology and history, hopes of returning to his homeland began to diffuse as the years went on.

It was the image of him writing for uninterrupted hours that romanticized my perception of narrative. As I learned Farsi during the academic year, studied English in the summer, and listened to Arabic at home, I began to observe how stories are told. Farsi, a profoundly poetic language birthing the likes of Rumi and Ferdowsi, uses verse and melody to observe mourning during the month of Ashura where Shiite Muslims gather as a community to grieve the death of Imam Hussein.

Arabic, an equally poetic language with an almost infinite vocabulary, narrates in hyperbole and metaphor, its written alphabet is entirely in calligraphy as exemplified in the Quran. I began to favor this practice – writing in long, artistic strokes – and expanded my vocabulary by reading copiously in the absence of modern entertainment. I learned how to be linguistically adaptable, listening to others in one language and translating stories to my parents in another language.

If life wasn’t complicated enough, my family moved to New Zealand when I was eleven. I was exposed to more languages; Māori, the indigenous spoken and written word of New Zealand, and British English with a smattering of Kiwi lingo that was foreign to both my parents. Piling on a growing identity crisis, I was now an Arab-American who speaks Farsi, in a school full of children speaking English with thick accents and unfamiliar words I had trouble understanding. To lessen the confusion and anxiety of when attempting to fit in, I once again turned to storytelling and writing, putting thoughts and observations on paper in an attempt to navigate questions on belonging. It wasn’t until an English high school teacher told me that I have a gift for writing did I begin to hone this skill.

Fast forward to many years later in New York City, I began speechwriting for a social justice leader. The delight I derived from reading content in law, sociology, and psychology, and developing the skill to incorporate such dense material as a captivating speech for a changemaker’s voice was immeasurable. I had found my craft. I discovered the power of storytelling for social change. Years spent observing various cultures threaded through multiple languages gave me my biggest gift; I can absorb a person’s voice into my pen and onto their paper. Telling EPA’s story through speeches for a Regional Administrator is not a task I take lightly. Lifting the voices of communities historically silenced or ignored bears important weight. It is the public’s glimpse into what we do to protect human health and the environment. It is how communities know they are heard. It is when people are assured that the federal government represents them. I consider it honorable to write EPA’s stories into speeches and I am so grateful that in a life woven with confusion, oddities and eccentrics, I have finally found where I belong.

About the Author

Sukayna Al-Aaraji

Speechwriter

Region 1

Sukayna has been at EPA Region 1 since 2022. Prior to this, she worked in New York City for a nonprofit organization serving New York’s most vulnerable communities. She has a bachelor’s degree in English and a postgraduate degree in Psychology from University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed here are intended to explain EPA policy. They do not change anyone’s rights or obligations. You may share this article. However, please do not change the title or the content, or remove EPA’s identity as the author. If you do make substantive changes, please do not attribute the edited title or content to EPA or the author.

EPA’s official web site is www.epa.gov. Some links on this page may redirect users from the EPA website to specific content on a non-EPA, third-party site. In doing so, EPA is directing you only to the specific content referenced at the time of publication, not to any other content that may appear on the same webpage or elsewhere on the third-party site, or be added at a later date.

EPA is providing this link for informational purposes only. EPA cannot attest to the accuracy of non-EPA information provided by any third-party sites or any other linked site. EPA does not endorse any non-government websites, companies, internet applications or any policies or information expressed therein.