EPA Researchers Inform Public Health Officials in Ohio on Variants of COVID-19 Virus through Wastewater Monitoring and Sequencing

Published November 1, 2021

Early in the pandemic, researchers at EPA’s laboratory in Cincinnati began looking for evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in municipal wastewater. Wastewater can contain indicators of COVID-19 infection in a community and this data can help inform public health decisions. For example, wastewater monitoring can help health officials know which communities need more access to testing, or predict when infection waves might be present in a community, often before anyone shows symptoms of the disease.

The team of researchers partnered with the Metropolitan Sewer District of Greater Cincinnati at first, and then worked with the Ohio Department of Health and Ohio EPA to provide data to show levels of virus in the southwest part of the state.

Since the beginning of this effort, the team of researchers has improved their monitoring approach and began looking at which variants might be present in the wastewater. This helps public health officials know when and where newer variants, like the Delta variant, come into a community and can help them determine the best ways to reduce exposure in the community.

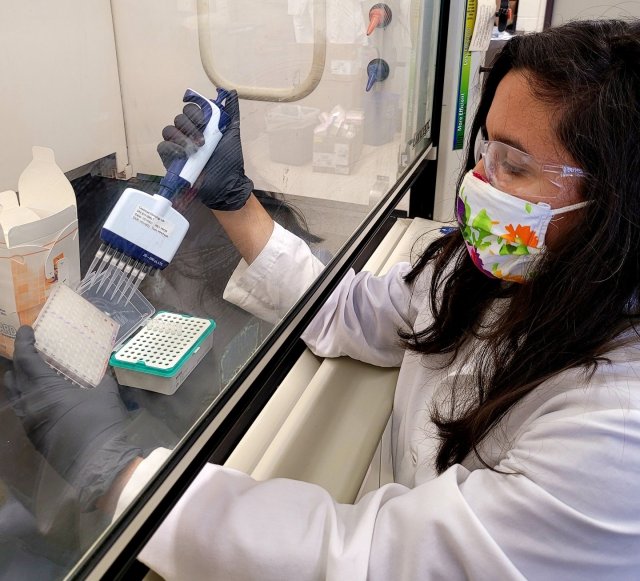

The researchers used high-throughput sequencing to gain information about what RNA sequences of the virus might be present in wastewater samples. Their approach includes concentrating the suspended solids in the samples, which according to EPA researcher Maitreyi Nagarkar, is where they see the majority of the SARS-CoV-2 viral material in wastewater.

Then the researchers extract the total RNA from the samples and use a procedure to amplify only the sequences from the SARS-CoV-2 genome. The researchers run this sample through a sequencer to identify specific sequences that are present. This is how they identify which variants might be circulating in the community.

“Because the entire SARS-CoV-2 genome has already been sequenced by a number of labs around the world, and genomes of new variants get sequenced as they emerge, we are able to identify what mutations in the genome sequence are associated with certain variants. These mutations in the genome sequence can lead to changes in the viral proteins, including the spike protein, and potentially alter the structure or function of the virus. The changes are particularly concerning if they allow the virus to become more infectious, or evade vaccine-induced immunity,” Nagarkar says.

She adds, “CDC has defined each of the variants of concern - like Alpha and Delta- based on certain characteristic amino acid changes, which we can retroactively identify by looking at the presence of the genome sequence data we obtain from our wastewater samples. We can make predictions about whether some of those variants are present in our wastewater samples based on whether their genome ‘signatures’ are present in the data.”

Last June, for example, the researchers were detecting limited amounts of SARS-CoV-2 in the wastewater as local cases were declining, but then in July they saw an increase in virus in the wastewater and that coincided with the number of cases that were being reported by the Ohio Department of Health. The wastewater samples showed increasing amounts of the RNA sequence associated with the Delta variant. Eventually, the Delta variant became the dominant virus the researchers were able to detect in the wastewater samples, which was supported by the limited clinical data available in the region.

“The only way to confirm the existence of a new variant is through sequencing clinical samples, but it is not yet feasible to sequence every infected individual in order to screen for the presence of new variants. Because we can use wastewater sequencing to detect the presence of previously unobserved mutations in clinical practice, as our analyses improve, we may be able to provide information that helps direct where clinical sequencing for identification of new variants could be prioritized,” says Nagarkar.

Wastewater monitoring has become a useful tool to make public health predictions. Often people are shedding virus before any symptoms occur. Knowing what a community is facing in advance helps public health officials make decisions like increasing contact tracing, encouraging wearing masks indoors, or increasing individual testing resources to a local community. These decisions can help reduce community exposure.

Nagarkar says, “Wastewater surveillance holds promise for monitoring any infectious disease that is shed in feces and readily detectable in wastewater. Because high-throughput sequencing has enabled very rapid understanding of the genomic sequences of any given pathogen, both sequencing or faster-turnaround quantitative methods could be implemented more rapidly to detect the next pathogen of concern.”

She adds, “There will likely need to be methodological and analytical adjustments as a new pathogen could be different in a variety of ways - for example, how long can it remain infectious in wastewater? How long is it shed in feces? How easy is it to detect and quantify using molecular techniques? - However, the fact that wastewater surveillance has been implemented so successfully and widely during this pandemic means that hopefully the infrastructure like sampling design, establishing partnerships to facilitate processing samples, and developing practices to analyze and take action based on resulting data, will be available the next time.”

EPA recently published a compendium that documents efforts across the country to monitor SARS-CoV-2 through wastewater sampling. The compendium also serves as a guide to others who are interested in implementing wastewater monitoring in the future by elaborating on funding, project management, results, and potential actions to prevent the continued spread of COVID-19. The compendium features a variety of case studies from across the country that showcase different approaches for implementing and analyzing wastewater-based surveillance to identify the presence of SARS-CoV-2.