EPA Researchers Use Novel Methods to Discover PFAS in Wildlife and Pets in Cape Fear River Region

Published December 2, 2024

Flowing for about 200 miles, the Cape Fear River runs from central North Carolina all the way to the Atlantic. The mouth of the river that feeds into the ocean is situated at the river’s namesake: Cape Fear. The river holds a history of trade and manufacturing since it allows commercial ships to reach the inland regions of the state. This attribute has also led to the expansion of industrial facilities along the Cape Fear River, potentially posing a threat to native ecological systems.

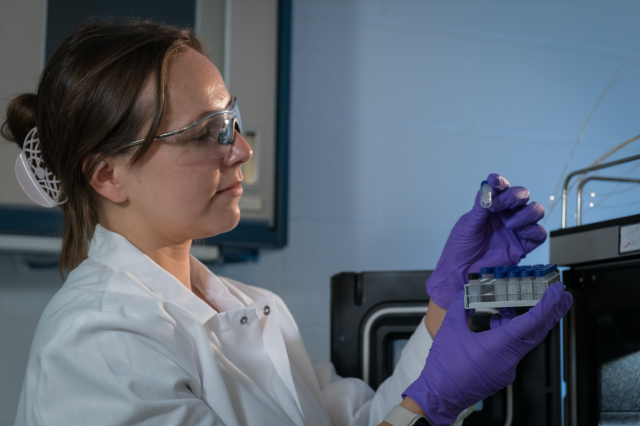

A growing body of scientific work on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), or “forever chemicals,” has linked these contaminants to manufacturing byproducts and chemical additives in consumer products, among other sources. EPA researchers are using state-of-the-art technology to detect and measure these compounds as a first step in treating PFAS contamination. One example is EPA’s use of non-targeted analysis techniques to detect multiple novel fluorinated species in wildlife and pets in the Cape Fear River region.

Workflow

EPA researcher Dr. Jackie Bangma catalyzed this study when she re-analyzed archived animal samples and found novel PFAS. Although several chemicals in the identified series (PFOx) had been characterized in wildlife and humans previously, the additional compounds had not yet been discovered in any samples from the Cape Fear River region. Bangma knew her team needed to look for evidence of these novel compounds that might have been missed in previous research.

With this charge, Bangma collaborated with EPA researchers Dr. Anna Robuck, Dr. James McCord, Dr. Jon Sobus, Dr. Thomas Jackson, and Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education fellows Shirley Pu and Dr. Jason Boettger to use non-targeted analysis techniques in their study. Non-targeted analysis offers an opportunity to find chemical compounds that may be outside standard analyte lists and libraries, while targeted analysis looks at small, pre-defined sets of chemicals.

“Targeted analysis is like looking outside with a handheld flashlight at night: you can really only see what you cast your beam on and what is within your line of sight,” Robuck said. “Non-targeted analysis is like walking outside on a bright sunny day: you can see everything, even if you didn’t know certain things would be outside.”

The team examined archived alligator, striped bass, horse, and dog serums, as well as archived seabird tissue data. Serums are blood-based samples that allow researchers to perform different biochemistry tests. The archived tissue data are rich, large-scale files from previous studies that researchers can revisit, reuse, or repurpose for different studies. The samples were collected from the Cape Fear River basin, the Roanoke River and Lake Waccamaw, and the seabirds were known to have stayed local to the Cape Fear River region throughout their lifespan.

Wading Through the Results

The researchers found three novel PFAS, all chemical byproducts from industry manufacturing, in the fish, alligator and seabird samples. One of these compounds was found in all eight seabird tissue samples. These three PFAS were not found in the dog or horse samples. Further, this study is the first to determine the presence of all three PFAS in wildlife serum. The researchers were able to provide quantitative values, or measurements, for one of the compounds in the series; however, the other two PFAS discovered did not have an existing standard to be able to measure against. Researchers used new methods to tentatively assign quantitative values to compare their findings across samples in a uniform way.

The researchers hypothesize that the presence of the PFAS series in alligators and striped bass, and their absence in horse and dog serum samples, may stem from the wildlife’s contact with river sediment. These species live in and feed from the river, while horses and dogs are disconnected from the river itself.

Looking Downstream

The Cape Fear River region is one of the only places where these PFAS have been found so far, possibly because researchers sampling in other industrial areas may not know to look for them. This research offers a starting point for future decision making now that scientists know these PFAS are in the region. For example, the striped bass species may be recreationally fished in the Cape Fear River, but at this point, there is little known about the risk associated with exposure or consumption of these compounds and the effects on people. Discovering these compounds can facilitate future fate and transport research, or the study of a contaminant’s destination and how it ends up there.

“Some of the seabirds were living on nesting islands almost 100 miles away from the contamination source,” Robuck said. “By finding the compounds in the first place, our work enables academics and federal or state agencies to dive in and figure out how these compounds travel and get into the wider environment.”

The study shows the power of non-targeted analysis and how researchers can mine archived data for different purposes to maintain a comprehensive picture of our environment.

Bangma and her team are hoping to examine the sediment in the Cape Fear River region to determine whether the compounds they found in the wildlife and surface water are present in other sources. Additional studies are needed to fully understand the potential impact of PFAS on both wildlife and humans in the Cape Fear River region.