Sowing Seeds for Cleaner Air: How EPA Researchers are Addressing Air Pollution at Chicago Area Schools

Published September 3, 2024

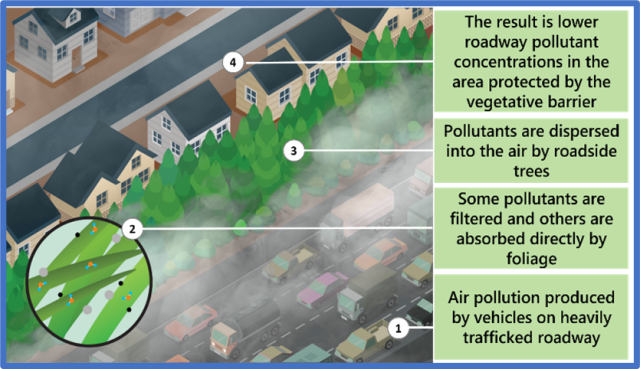

EPA scientists are partnering with organizations in the greater-Chicago metropolitan area to assess the use of vegetative barriers in mitigating the effects of nearby roadway air pollution and improving air quality near schools. Vegetative barriers, such as roadside trees and foliage, can clean air by trapping pollutants on leaves and branches or forcing air up and away from people.

EPA’s Richard Baldauf and the EPA Chicago Vegetative Barrier Project team—Jennifer Tyler, Sheila Batka, Kathy Kowal, Yulissa Aguilar, and Megan Gavin— work with three Chicago-area schools located near major roadways in a study using trees and other vegetative barriers to protect schools from roadway air pollution.

“Chicago represents many cities across the U.S. where schools are located near large roadways,” said Baldauf, who is co-leading the study. “By properly planting vegetative barriers next to the schools, we hope to see improvements in air quality inside and outside the schools.”

EPA is collaborating on this project with the University of Illinois, the U.S. Forest Service, the City of Chicago, the Chicago-based Environmental Law and Policy Center and The Morton Arboretum. Researchers are also partnering with the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) to measure noise levels outside the schools.

EPA scientists measured air quality inside and outside the schools during spring 2024. Though some trees have been planted at two schools by The Morton Arboretum and IDOT, more air quality measurements can be taken as the vegetation grows once the barriers are completely planted.

During the study, researchers use air sensors to measure pollutants commonly released in motor vehicle exhaust, including particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide and black carbon, which is a form of particulate matter. The researchers also collect meteorological data, including wind speed and direction, temperature, humidity, and precipitation measurements.

“Appropriately selected and maintained bushes and trees along roads have been shown to reduce air pollution exposures,” Baldauf said. “Plants used as vegetative barriers need to be suitable for all local weather situations and keep their foliage year-round so there are no gaps or large spaces.”

University of Illinois professor Dr. Mary Patricia McGuire and a small team of graduate students are working with The Morton Arboretum and the EPA to provide landscape architecture expertise to the project and design vegetation buffer prototypes that will be tested, refined and implemented at school sites.

“Collaboration across our team has been essential for bridging science and implementation,” McGuire noted. “As landscape architects, one of our key contributions is to work in the middle as translators and mediators between science, the site conditions, and the community. The visualizations we create allow the whole team, including the school community, to see, discuss and tweak the design together so that the designed buffer goes beyond air quality function to also address questions of aesthetics, safety, and other benefits of school greening.”

Tree and vegetation buffers are a fairly new design technology in American cities but could be a critical asset in the future as researchers expand their understanding of how to effectively integrate them into green infrastructures. EPA’s collaboration with local and university partners to pull in a breadth of knowledge and input is essential to identifying best practices for later vegetative barrier design and implementation.

EPA in Action

The project includes an educational and environmental awareness component. During their visits to the schools, the researchers led air quality educational sessions with students and demonstrated the air monitoring equipment being used in the study.

“Approximately 600 students participated in the educational sessions and showed a lot of interest in how the sensors worked, what they were measuring, and how the issue of air and noise pollution in their schools could be addressed,” Baldauf said. “Involving and informing students and teachers is a priority because this project relies on community collaboration.”

Just Keep Growing

Baldauf and his collaborators plan to continue conducting measurements after the vegetative barriers grow so the team can assess their impact on air and noise quality. Study results are expected to be available one year after completion of the vegetation sampling and will be shared with the participating schools.

By collecting air quality samples using air sensors and meteorological equipment, EPA scientists and their project partners aim to expand understanding of the ways that vegetative barriers can impact air quality and noise pollution near schools and other buildings, promote learning and community engagement about air quality and trees, and create cleaner air for school communities.

This article was written by Sarah Whichello, Oak Ridge Associated Universities Research participant with EPA.