Frequently Asked Questions

- Drinking Water

- Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF)

- Enforcement

- Aquifer Impacts

- Defueling

- Community Engagement

Drinking Water

Q: What petroleum contaminants were found in Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickham (JBPHH) drinking water?

A: The main petroleum-related contaminants that were found in JBPHH drinking water are a group of contaminants collectively known as “Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons” or TPH. Petroleum Hydrocarbons are a large class of chemicals that are the primary compounds found in common fuels such as kerosene, gasoline, diesel, motor oil, and different jet fuels, including JP-5. Each type of fuel consists of a slightly different mixture of hundreds of types of petroleum hydrocarbons.

A subset of TPH compounds (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene) are regulated under EPA’s Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). TPH is not regulated under the SDWA.

As part of the long-term monitoring plan, the Navy continues to sample residences, businesses, schools, and clinics served by the water system as well as the distribution system for TPH. Since the lifting of the drinking water advisory, TPH has not been detected at levels above the State of Hawai‘i Environmental Action Levels (266 µg/L).

Q: Why doesn’t EPA regulate jet fuel in drinking water?

A: EPA regulates over 90 contaminants that may be found in drinking water under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). Contaminants like the jet fuel in found in the JBPHHH drinking water in 2021 are not expected to be found in public drinking water systems. The SDWA requires water systems to conduct routine monitoring for the regulated contaminants. These include several contaminants sometimes found in jet fuel, such as benzene, xylene, toluene, and other specific organic contaminants.

The Navy has performed regular testing for the presence of fuel in the JBPHH drinking water system since December 2021 and will continue to sample residences, businesses, schools, clinics, and the distribution system as part of the Long-Term Monitoring Plan, with an end date of March 2024.

Q: Why doesn’t the EPA take over the Navy’s Drinking Water system?

A: Federal and state regulatory agencies do not own or operate public drinking water systems. In Hawai‘i, EPA has granted primary enforcement authority to the Hawai‘i Department of Health (DOH) for ensuring public water systems (PWSs) in the State meet SDWA requirements. JBPHH is a regulated PWS.

As it did during the JBPHH drinking water emergency, DOH has the authority to issue advisories, warnings and orders until drinking water systems are back in compliance. Although the primary enforcement of the SDWA is delegated to the State, EPA retains oversight responsibility and the ability to take formal enforcement actions, issue orders, and levy penalties if the situation warrants. In April 2021, EPA conducted a drinking water inspection of the JBPHH PWS and has been working with the Navy to fix issues.

Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF)

Q: What does EPA know about the AFFF system, how much AFFF has been stored, discharged and remains at Red Hill, and AFFF concentrate spill? Why doesn’t EPA have detailed information about the AFFF release event? Aren’t you responsible for protecting human health and the environment?

A: It is important for EPA to understand not only the November 29, 2022, AFFF release and the Navy’s efforts to investigate, but all other AFFF releases. If PFAS is found in an underground source of drinking water, it has the potential to pose unacceptable risk to human health and the environment. For this reason, the EPA has sent the Navy a comprehensive Request for Information investigating the cause, response and impacts of the AFFF spill and any other past sources or releases of PFAS. We received a response last month, including the attached letter and list of historic releases.

EPA has asked the Navy to sample all active and inactive sources for the JBPHH water system for PFAS by April 30th. Past Navy sampling has detected the presence of PFAS at the Aiea Halawa source, but not at the Waiawa and Red Hill sources, when using EPA-approved drinking water methods. Sample results are based on the sensitivity of analytical methods. EPA is currently working to increase the sensitivity of its drinking water methods to detect PFAS at lower levels.

We are working with the Navy to release additional documentation to the public. In the interim, EPA continues to move forward with our investigation of the incident with the information provided.

Q: Why isn’t all data (e.g. AFFF records, video of the spill, and PFAS sampling) shared with the public?

A: The Navy and DLA are required to make data generated under the 2023 Administrative Consent Order electronically available to the public on their website. EPA has followed up with the Navy and they will be sharing validated PFAS data on a weekly basis on the Joint Base Pearl Harbor Hickam Safe Water website. However, they have requested more time to publicly release AFFF records and have claimed the video to be confidential pending their internal investigation.

Enforcement

Q: What has EPA done to investigate Red Hill since the 2021 release?

EPA conducted several inspections throughout 2022 to comprehensively evaluate the Navy’s compliance with Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasure, Underground Storage Tank, and Safe Drinking Water Act requirements. EPA is working with the Navy to address findings related to the 2023 Administrative Consent Order to minimize risk and impacts of any further leaks from tanks and pipes and enhance the on-base drinking water system.

EPA has also issued multiple information request letters since 2021 as part of our ongoing investigation into the status of facility, cause of any releases, and assessment of water quality.

Q: Is the Navy still under the 2015 Agreed Order of Consent (AOC) and is the EPA working on another?

A: Yes, the Navy is still required to comply with requirements in the 2015 AOC. Work under sections 6 and 7 of the AOC Statement of Work related to investigation of releases and groundwater protection are active.

The 2023 Administrative Consent Order is focused on the time period leading up to defuel and closure and provides an enforceable oversight agreement for the safe defueling and closure of the Red Hill Facility, and protection of the Navy’s drinking water system on O’ahu.

Q: Why wasn’t the public consulted when drafting the 2023 Order?

A: EPA needed to immediately require the Navy to commit to certain aspects of transparency and oversight structure in order to formalize ongoing closure work that EPA was involved with. Therefore, EPA negotiated a draft Consent Order with the Navy as soon as possible. EPA shared the proposed order with all stakeholders, including the public, in late December 2022 and public comment was received through February 6, 2023, on regulations.gov.

Aquifer Impacts

Q: How does EPA know that Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) detections at Aiea Wells are not related to any/all historic Red Hill fuel spills?

A: EPA evaluated the available data from the Honolulu Board of Water Supply (BWS) and the Navy and we have concluded that Red Hill is an unlikely source for the following reasons:

- The chemical properties of the PAH compounds found in the BWS wells prevent them from easily dissolving into groundwater and traveling far from where they were released into the environment. They are relatively “sticky” compounds that absorb to clays and organic matter in the soil and aquifer, which greatly reduces their mobility in the subsurface.

Similar to how smoke from a chimney disperses downwind, groundwater contamination disperses and becomes more diluted downstream (downgradient) from its source. Given the 1.7 mile separation distance, EPA expects groundwater contamination from Red Hill would be highly diluted and dispersed before reaching the Aiea wells. However, some of the PAHs found in the Aiea wells were detected near their solubility limit. This means the PAHs detected in the Aiea Wells likely came from a source very close to the wells (or perhaps entered the wells directly through a compromised surface seal) rather than from Red Hill. - As presented at the FTAC in October 2024, the PAHs detected in the Aiea wells are likely a pyrogenic source (from burning) and not likely a petrogenic source (from petroleum) and overall, have a different chemical profile than the PAH contamination found at Red Hill. Example: The PAHs detected at the Aiea wells are dominated by high molecular-weight PAHs while low-molecular weight PAHs are most prevalent at Red Hill.

- If Red Hill had been a source of the BWS samples, we would have expected to see other petroleum hydrocarbon contamination as well as the PAHs the BWS detected. Example: TPH, methylnaphthalenes, and other chemicals are found at Red Hill and not in the May and June samples from Aiea Wells.

- If this were a large plume that traveled nearly 2 miles, we would expect it to persist, and it hasn’t. PAHs were detected on two events and not before or after. EPA is not aware of a site where a PAH plume in groundwater has detached and migrated away from its source, which would be necessary to explain the transient detections.

- Groundwater plumes follow a pattern. During and immediately following a petroleum release, the plume grows rapidly. After the source of release is stopped, the plume stops growing, stabilizes and then begins to contract. Following the November 2021 release from Red Hill, the farthest detections we saw were no more than ¼ to ½ mile from Red Hill. Since that time, the extent and magnitude of contamination have decreased, and current impacts are limited to the tank gallery area. Many of the Navy’s groundwater monitoring wells serve as sentinel wells and provide early warning if contamination plumes are heading toward BWS drinking water wells. EPA is not seeing indications of plume migration in the sentinel wells.

More information can be found in the DOH FTAC presentation PowerPoint Presentation.

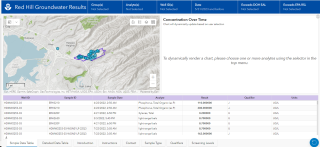

Q: What are regulatory agencies doing to understand the impacts to the aquifer from Red Hill contamination? What GW monitoring trends are you seeing over time?

A: The agencies evaluate weekly groundwater and soil vapor data to assess impacts to the aquifer. In addition, the agencies oversee the Navy’s investigation efforts, including installation of new groundwater monitoring wells, which will expand the Red Hill groundwater monitoring well network. Since the November 2021 release, Navy has installed 7 additional monitoring wells and currently has 4 additional installations underway to improve understanding of water movement. The Navy plans to install up to 11 additional groundwater monitoring wells by end of 2023 (contingent on offsite access).

The extent of groundwater contamination (i.e., areas where contaminant concentrations exceed Hawaii’s Environmental Action Levels [EALs]) near the Red Hill facility increased after the 2021 fuel releases. Contamination remains in the tank area but the frequency of exceedances of Hawaii’s EALs in sampling locations away from the tank area has decreased in recent months. This suggests groundwater contamination has decreased since the 2021 releases.

Q: Are other compounds that may have been stored at the facility being tested for, like rocket fuels?

A: Groundwater samples from monitoring wells at and near the Red Hill facility are collected weekly from approximately 23 wells and tested for more than 100 constituents. Constituents include petroleum hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds, semi-volatile organic compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, lead and PFAS. Additionally, groundwater is sampled quarterly for petroleum hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds, semi-volatile organic compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, fuel additives and lead. Constituents were chosen because they may be present in or are associated with fuels stored at Red Hill, but the testing may also detect contamination from other sources.

Q: How far has contamination spread in the aquifer? Is it moving toward our drinking water?

A: Groundwater contamination has been consistently detected in the Red Hill tank area. Contaminants believed to be associated with the Red Hill facility have been detected less consistently at outlying groundwater monitoring wells located about ¼ to ½ mile from the facility. Additional monitoring wells are planned further away from the Red Hill facility to determine whether contaminants are present beyond the existing monitoring well network.

Q: How is the Navy cleaning up the contamination in the aquifer? What is the process & timeline?

A: Remediation efforts have included removal of fuel from Red Hill Shaft, pump, and treatment of four million gallons of groundwater per day from Red Hill Shaft, excavation of soil contaminated by the November 2021 fuel spill in and near Adit 3, and excavation of soil contaminated by the November 2022 AFFF spill. EPA and DOH are evaluating the benefits of continuing the Red Hill Shaft pumping effort. EPA and DOH will decide on the need for additional cleanup of contamination from the 2021 releases and past releases after additional investigation and monitoring work is completed in 2023 or 2024.

Defueling

Q: What is EPA doing to make sure there isn’t another Red Hill fuel release during defueling?

A: EPA is applying all applicable regulatory and statutory authorities for protection of human health to the planned defueling work. Program experts from multiple regulatory programs continue to provide day-to-day oversight of the facility, and a dedicated “Red Hill Team” has been established to ensure timely, consistent, and accurate responses to Navy defueling plans.

Most importantly, EPA is ensuring the Navy’s facility repairs and operational changes eliminate conditions that resulted in the May 6 and November 20 (2021) spills. This involves detailed review a of the planned repairs and alterations to the facility as presented in the third-party engineering reports assessing facility readiness. EPA and DOH have provided comments and will continue to review the Navy’s plans associated with Red Hill.

Q: What will EPA regulatory authority be after Red Hill closure? Where will the fuel go and what the oversight will be?

A: The Navy’s Defueling Plan states that fuel from Red Hill may move to the Upper Tank Farm (UTF), on-island storage at Contractor Owned/Contractor Operated (COCO) facilities, and via tanker to the West Coast of the United States. The Navy will be held to all applicable environmental regulations for future cleanup, fuel movement, and storage activities.

Q: How will reports and progress on defueling be relayed to the public?

A: EPA will post or link to publicly available Navy deliverables in preparation for defueling. EPA has stressed the importance of engaging with the public in regular and meaningful ways with the Navy’s Joint Task Force.

Community Engagement

Q: How can the community and stakeholders be involved in resolving the Red Hill crisis?

A: The EPA is committed to sharing information on Red Hill activities with the public. We will be doing so via:

- Email Blasts Sharing Relevant EPA Oversight Actions

- Red Hill in Focus Webinar Series

- Hosting Public Meetings

- Public Engagement Website

- Sharing Opportunities for the Public to Provide Input in EPA Decisions

Additionally, the Red Hill Community Involvement Plan (CIP) (pdf) was created to elevate community concerns and lay out best practices for sharing information and receiving input from the public. The CIP was shaped by the input of individuals and stakeholders.