Climate Change Indicators: Cold-Related Deaths

This indicator presents data on deaths classified as “cold-related” in the United States.

Key Points

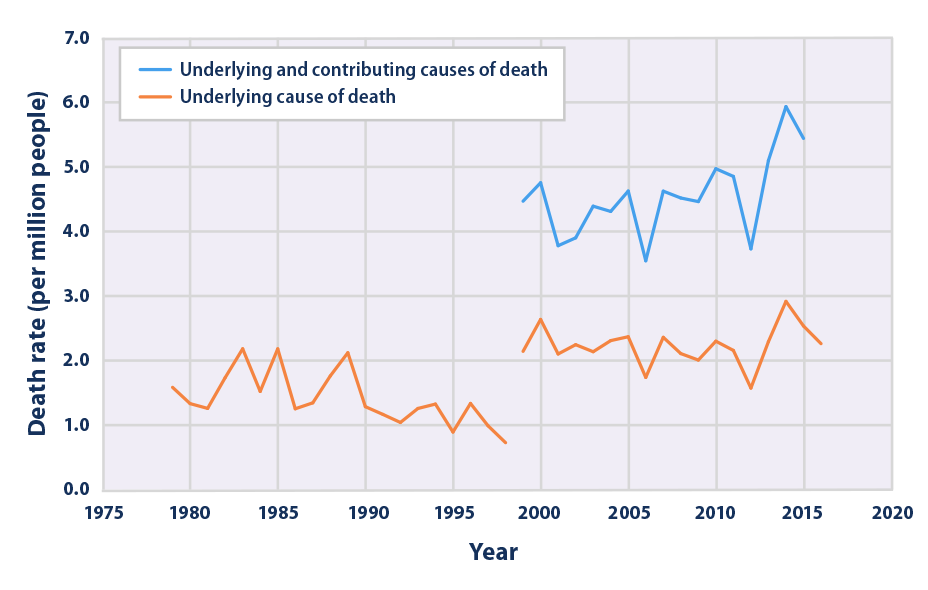

- Between 1979 and 2016, the death rate as a direct result of exposure to cold (underlying cause of death) generally ranged from 1 to 2.5 deaths per million people, with year-to-year fluctuations (see Figure 1). Overall, a total of more than 19,000 Americans have died from cold-related causes since 1979, according to death certificates.

- For years in which the two records overlap (1999–2015), accounting for those additional deaths in which cold was listed as a contributing factor results in a higher death rate—more than double for most years—compared with the estimate that only includes deaths where cold was listed as the underlying cause (see Figure 1).

- While increases in deaths are generally associated with colder temperatures, some winter deaths are due to factors other than exposure to cold conditions. For example, winter is typically flu season. In other cases, even if cold exposure contributes to a death, it may not be reported as “cold-related” on a death certificate. These limitations, as well as year-to-year variability in the data and a change in classification codes in the late 1990s, make it difficult to determine whether the United States has experienced a meaningful increase or decrease in deaths classified as “cold-related” over time.

Background

In recent years, U.S. death rates in winter months have been 8 to 12 percent higher than in non-winter months.1 Much of this increase relates to seasonal changes in behavior and the human body, as well as increased exposure to respiratory diseases. Cold temperatures can also worsen pre-existing medical conditions such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. For example, death rates from heart attacks increase as temperatures drop, likely due to the way cold affects blood circulation, blood vessels, and other factors.2,3 Even moderately cold days can increase the risk of death for many people. People exposed to extremely cold conditions can also suffer from direct effects such as frostbite and potentially deadly hypothermia, especially in places where people are not accustomed to cold temperatures.

Certain population groups face higher risks of cold-related illness or death. For example, occupational groups that work outdoors during winter months, such as agricultural workers, construction workers, and electricity and pipeline utility workers, face higher risks of exposure to cold.4 Others at risk include older adults, infants, people with pre-existing medical conditions, people taking medications or using drugs (especially alcohol) that make them more susceptible to cold effects, homeless people, and those with inadequate winter clothing or home heating.5

Unusually cold winter temperatures have become less common across the contiguous 48 states in recent decades,6 particularly very cold nights (see the High and Low Temperatures indicator). Extreme cold waves are likely to continue to decrease as winter temperatures increase in the future.7 This winter warming is expected to reduce the number of direct cold-related deaths, but the decrease is projected to be smaller than increases in heat-related deaths (see the Heat-Related Deaths indicator) in most regions.8 This is because some of the factors that lead to higher death rates in the winter are not particularly sensitive to climate change,9 because extreme heat has a more immediate and direct effect on death rates than extreme cold,10 and because the solutions to protect against cold exposure (such as staying indoors, wearing more clothing, turning on the heat) are more widely accessible than protection against extreme heat.11 Cold-related death rates can change as communities strengthen their cold weather plans and take other steps to protect vulnerable people during cold winter months.

About the Indicator

Like the Heat-Related Deaths indicator, this indicator shows the annual rate for deaths classified by medical professionals as “cold-related” in the United States based on death certificate records. Every death is recorded on a death certificate, where a medical professional identifies the main cause of death (also known as the underlying cause), along with other conditions that contributed to the death. These causes are classified using a set of standard codes. Dividing the annual number of deaths by the U.S. population in that year, then multiplying by one million, will result in the death rates (per million people) that this indicator shows.

Figure 1 shows cold-related death rates using two methods. One method shows deaths for which exposure to excessive natural cold was stated as the underlying cause of death from 1979 to 2016. The other data series shows deaths for which cold was listed as either the underlying cause or a contributing cause, based on a broader set of data that, at present, can only be evaluated for the years 1999 to 2015. For example, in a case where cardiovascular disease was determined to be the underlying cause of death, cold could be listed as a contributing factor because it can make the individual more susceptible to the effects of this disease.

About the Data

Indicator Notes

Several factors influence the ability of this indicator to estimate the true number of deaths associated with exposure to cold temperatures. Some cold-related deaths are not identified as such by the medical examiner and might not be properly coded on the death certificate. In many cases, the medical examiner might classify the cause of death as a cardiovascular or respiratory disease, not knowing for certain whether cold was a contributing factor. Furthermore, deaths can occur from exposure to cold (either as an underlying cause or as a contributing factor) that is not classified as extreme and therefore is often not recorded as such. These factors are similar to the factors that likely lead to undercounting of heat-related deaths (see the Heat-Related Deaths indicator), except that the effects of cold on the body tend to persist for longer than the effects of heat,14 which could make it even more difficult to connect deaths to exposures.

Classifying a death as “cold-related” does not mean that cold temperatures were the only factor that caused or contributed to the death, as pre-existing medical conditions can significantly increase an individual’s susceptibility to cold temperatures. Other important factors, such as the overall vulnerability of the population, and the extent to which people have adapted and acclimated to cold temperatures, can also affect trends in cold-related deaths. Some deaths classified as “cold-related” reflect human behavior more than weather conditions—for instance, deaths in which alcohol abuse increased a person's susceptibility to cold weather, falling into cold water (which can cause hypothermia, even in non-winter months), or getting lost on a wilderness excursion. This indicator includes these types of deaths.

Data Sources

Data for this indicator were provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The 1979–2016 underlying cause data in Figure 1 are publicly available through the CDC WONDER database at: https://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html. The 1999–2015 analysis in Figure 1 was developed by using data provided by CDC’s Environmental Public Health Tracking Program.

Technical Documentation

References

1. CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2017. CDC WONDER database: Compressed mortality file, underlying cause of death. Monthly all-cause mortality for 2011–2016. Accessed March 2018. https://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html.

2. Gasparrini, A., et al. 2015. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: A multicountry observational study. The Lancet 386(9991):369–375.

3. Medina-Ramón, M., and J. Schwartz. 2007. Temperature, temperature extremes, and mortality: A study of acclimatization and effect modification in 50 U.S. cities. Occup. Environ. Med. 64(12):827–833.

4. Sarofim, M.C., S. Saha, M.D. Hawkins, D.M. Mills, J. Hess, R. Horton, P. Kinney, J. Schwartz, and A. St. Juliana. 2016. Chapter 2: Temperature-related death and illness. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://health2016.globalchange.gov.

5. Berko, J., D.D. Ingram, S. Saha, and J.D. Parker. 2014. Deaths attributed to heat, cold, and other weather events in the United States, 2006–2010. National Health Statistics Reports No. 76. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr076.pdf.

6. USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program). 2017. Climate science special report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, volume I. Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock (eds.). https://science2017.globalchange.gov. doi:10.7930/J0J964J6.

7. USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program). 2017. Climate science special report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, volume I. Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock (eds.). https://science2017.globalchange.gov. doi:10.7930/J0J964J6.

8. Sarofim, M.C., S. Saha, M.D. Hawkins, D.M. Mills, J. Hess, R. Horton, P. Kinney, J. Schwartz, and A. St. Juliana. 2016. Chapter 2: Temperature-related death and illness. The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://health2016.globalchange.gov.

9. Sarofim, M.C., S. Saha, M.D. Hawkins, D.M. Mills, J. Hess, R. Horton, P. Kinney, J. Schwartz, and A. St. Juliana. 2016. Chapter 2: Temperature-related death and illness. The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://health2016.globalchange.gov.

10. Sarofim, M.C., S. Saha, M.D. Hawkins, D.M. Mills, J. Hess, R. Horton, P. Kinney, J. Schwartz, and A. St. Juliana. 2016. Chapter 2: Temperature-related death and illness. The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://health2016.globalchange.gov.

11. Barnett, A.G., S..Hajat, A. Gasparrini, and J. Rocklöv. 2012. Cold and heat waves in the United States Environ. Res. 112:218–224.

12. CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2018. Mortality Data on CDC WONDER: Underlying cause-of-death: All ages deaths from compressed mortality. Accessed March 2018. https://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html.

13. CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2017. Monthly national totals provided by National Center for Environmental Health staff in March 2018, based on contributing causes of death with exclusion criteria applied.

14. Gasparrini, A., et al. 2015. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: A multicountry observational study. The Lancet 386(9991):369–375.