Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture and Food Supply

There are nearly two million farms in the United States, and more than half the nation’s land is used for agricultural production.1 The number of farms has been slowly declining since the 1930s,2 though the average farm size has remained about the same since the early 1970s.3 Many industries, such as food service and food manufacturing, are connected to agriculture and depend on farms.

-

Drought. Since early 2020, the U.S. Southwest has been experiencing one of the most severe long-term droughts of the past 1,200 years. Multiple seasons of record low precipitation and near-record high temperatures were the main triggers of the drought. 37

-

Wildfires. Some tribal communities are particularly vulnerable to wildfires due to their often-remote locations and lack of firefighting resources and staff.38 In addition, because wildfire smoke can travel long distances from the source fire, its effects can be far reaching, especially for people with certain medical conditions or who spend long periods of time outside.

-

Decreased crop yields. Rising temperatures and carbon dioxide concentrations may increase some crop yields, but the yields of major commodity crops (such as corn, rice, and oats) are expected to be lower than they would in a future without climate change.39

-

Heat stress. Dairy cows are especially sensitive to heat stress, which can affect their appetite and milk production. In 2010, heat stress lowered annual U.S. dairy production by an estimated $1.2 billion.40

-

Soil erosion. Heavy rainfalls can lead to more soil erosion, which is a major environmental threat to sustainable crop production.41

Agriculture is very sensitive to weather and climate.4 It also relies heavily on land, water, and other natural resources that climate affects.5 While climate changes (such as in temperature, precipitation, and frost timing) could lengthen the growing season or allow different crops to be grown in some regions,6 it will also make agricultural practices more difficult in others.

The effects of climate change on agriculture will depend on the rate and severity of the change, as well as the degree to which farmers and ranchers can adapt.7 U.S. agriculture already has many practices in place to adapt to a changing climate, including crop rotation and integrated pest management. A good deal of research is also under way to help prepare for a changing climate.

Learn more about climate change and agriculture:

- Top Climate Impacts on Agriculture

- Agriculture and the Economy

- Population Impacts

- What We Can Do

- Related Resources

Top Climate Impacts on Agriculture

Climate change may affect agriculture at both local and regional scales. Key impacts are described in this section.

1. Changes in Agricultural Productivity

Climate change can make conditions better or worse for growing crops in different regions. For example, changes in temperature, rainfall, and frost-free days are leading to longer growing seasons in almost every state.8 A longer growing season can have both positive and negative impacts for raising food. Some farmers may be able to plant longer-maturing crops or more crop cycles altogether, while others may need to provide more irrigation over a longer, hotter growing season.

Air pollution may also damage crops, plants, and forests.9 For example, when plants absorb large amounts of ground-level ozone, they experience reduced photosynthesis, slower growth, and higher sensitivity to diseases.10

Climate change can also increase the threat of wildfires. Wildfires pose major risks to farmlands, grasslands, and rangelands.11

Temperature and precipitation changes will also very likely expand the occurrence and range of insects, weeds, and diseases.12 This could lead to a greater need for weed and pest control.13

Pollination is vital to more than 100 crops grown in the United States.14 Warmer temperatures and changing precipitation can affect when plants bloom and when pollinators, such as bees and butterflies, come out.15 If mismatches occur between when plants flower and when pollinators emerge, pollination could decrease.16

Heat and humidity can also affect the health and productivity of animals raised for meat, milk, and eggs.17

2. Impacts to Soil and Water Resources

Climate change is expected to increase the frequency of heavy precipitation in the United States, which can harm crops by eroding soil and depleting soil nutrients.19

Heavy rains can also increase agricultural runoff into oceans, lakes, and streams which can harm water quality.20 Runoff can carry nutrients, fertilizer, and pesticides into neighboring water bodies.

When coupled with warming water temperatures brought on by climate change, runoff can lead to depleted oxygen levels in water bodies. This is known as hypoxia. Hypoxia can kill fish and shellfish. It can also affect their ability to find food and habitat, which in turn could harm the coastal societies and economies that depend on those ecosystems.21

Sea level rise and storms also pose threats to coastal agricultural communities. These threats include erosion, agricultural land losses, and saltwater intrusion, which can contaminate water supplies.22 Climate change is expected to worsen these threats.23

3. Agricultural Workers' Health

Agricultural workers face several climate-related health risks. These include exposures to heat and other extreme weather, more pesticide exposure due to expanded pest presence, disease-carrying pests like mosquitos and ticks, and degraded air quality.24 Language barriers, lack of health care access, and other factors can compound these risks.25 Higher temperatures and resulting heat stress are affecting farmworker safety and productivity, which can affect earnings and their own food security.26

Learn more about climate change and the health of workers.

For more specific examples of climate change impacts in your region, please see the National Climate Assessment.

Agriculture and the Economy

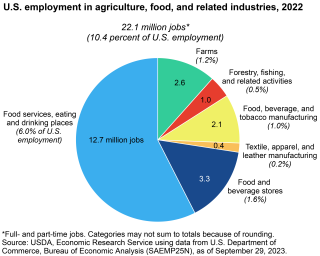

Agriculture contributed more than $1.53 trillion to the U.S. gross domestic product in 2023.27 In 2022, the sector accounted for 10.4 percent of total U.S. employment.28 These include not only on-farm jobs, but also jobs in food service and other related industries. Food service makes up the largest share of these jobs at 12.7 million.29

Cattle, corn, dairy products, and soybeans are the top income-producing commodities.30 The United States is a key exporter of soybeans, other plant products, tree nuts, animal feeds, beef, and veal.31

Population Impacts

Many hired crop farmworkers are foreign-born people from Mexico and Central America.32 Most hired crop farmworkers are not migrant workers; instead, they work at a single location within 75 miles of their homes.33 Many hired farmworkers can be more at risk of climate health threats due to social factors, such as language barriers and health care access.

Climate change could affect food security for some households in the country. Most U.S. households are currently food secure. This means that all people in the household have enough food to live active, healthy lives. In 2023, 13.5 percent (18.0 million households) were food insecure.34 These households faced a lack of resources that resulted in difficulty providing enough food for all their members. U.S. households with above-average food insecurity include those with an income below the poverty threshold, those headed by a single woman, and those with Black or Hispanic owners and lessees.35

Climate change can also affect food security for some Indigenous peoples in Hawai'i and other U.S.-affiliated Pacific islands. Climate impacts like sea level rise and more intense storms can affect the production of crops like taro, breadfruit, and mango.36 These crops are often key sources of nutrition and may also have cultural and economic importance.

What We Can Do

We can reduce the impact of climate change on agriculture in many ways, including the following:

- Incorporate climate-smart farming methods. Farmers can use climate forecasting tools, plant cover crops, and take other steps to help manage climate-related production threats.

- Join AgSTAR. Livestock producers can get help in recovering methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from biogas created when manure decomposes.

- Reduce runoff. Agricultural producers can strategically apply fertilizers, keep their animals out of streams, and take more actions to reduce nutrient-laden runoff.

- Boost crop resistance. Adopt research-proven ways to reduce the impacts of climate change on crops and livestock, such as reducing pesticide use and improving pollination.

- Prevent food waste. Stretch your dollar and shrink your carbon footprint by planning your shopping trips carefully and properly storing food. Donate nutritious, untouched food to food banks and those in need.

See additional actions you can take, as well as steps that companies can take, on EPA’s What You Can Do About Climate Change page.

Related Resources

- Fifth National Climate Assessment, Chapter 11: “Agriculture, Food Systems, and Rural Communities."

- National Agricultural Center. Provides agriculture-related news from all of EPA through a free email subscription service.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service. Produces research, information, and outlook products to enhance people’s understanding of agriculture and food issues.

- USDA Environmental Quality Incentives Program. Provides financial and technical assistance to agricultural producers to address natural resource concerns.

- USDA Climate Hubs. Connects farmers, ranchers, and land managers with tools to help them adapt to climate change impacts in their area.

- USDA Rural Development. Promotes economic development in rural communities. Provides loans, grants, technical assistance, and education to agricultural producers and rural residents and organizations.

- National Integrated Drought Information System. Coordinates U.S. drought monitoring, forecasting, and planning through a multi-agency partnership. The U.S. Drought Monitor assesses droughts on a weekly basis.

- Sustainable Management of Food. Provides tools and resources for preventing and reducing wasted food and its associated impacts over the entire life cycle.

- Resources, Waste, and Climate Change. Learn how reducing waste decreases our carbon footprint and what business, communities, and individuals can do.

Endnotes

1 U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Economic Research Service (ERS). (2024). Ag and food statistics: Charting the essentials. Land and Natural Resources. Retrieved 1/10/2025.

2 USDA, ERS. (2022). Ag and food statistics: Charting the essentials. Farming and farm income. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

3 USDA, ERS. (2022). Ag and food statistics: Charting the essentials. Farming and farm income. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

4 Walsh, M.K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture (pdf) (29.1 MB). USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 1.

5 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 393.

6 Walsh, M.K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture (pdf) (29.1 MB). USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 22.

7 Bolster, C.H., et al (2023). Ch. 11. Agriculture, food systems, and rural communities. In: Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA. p. 11-20.

8 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 401.

9 Nolte, C.G., et al. (2018). Ch. 13: Air quality. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 513.

10 EPA. (2022). Ecosystem effects of ozone pollution. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

11 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 401.

12 Ziska, L., et al. (2016). Ch. 7: Food safety, nutrition, and distribution. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 197.

13 Ziska, L., et al. (2016). Ch. 7: Food safety, nutrition, and distribution. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 197.

14 USDA. Pollinators. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

15 Walsh, M.K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture (pdf) (29.1 MB). USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 40.

16 Walsh, M.K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture (pdf) (29.1 MB). USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 40.

17 Walsh, M.K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture (pdf) (29. 1 MB). USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 20.

18 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 405.

19 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 404.

20 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 404.

21 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 405.

22 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 405.

23 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 405.

24 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, pp. 247–286.

25 Hernandez, T., and S. Gabbard. (2019). Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2015–2016: A demographic and employment profile of United States farmworkers. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Washington, DC, pp. 10–11 and pp. 40–45.

26 Bolster, C.H et al (2023). Ch. 11. Agriculture, food systems, and rural communities. In: Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA., p. 11-16.

27 USDA, ERS. (2024). Ag and food statistics: Charting the essentials. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

28 USDA, ERS. (2024). Ag and food statistics: Charting the essentials. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

29 USDA, ERS. (2024). Ag and food statistics: Charting the essentials. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

30 USDA, ERS. (2024). Farming and Farm Income. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

31 USDA, ERS. (2024). Farming and Farm Income. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

32 USDA, ERS. (2023). Farm Labor. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

33 USDA, ERS. (2023). Farm Labor. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

34 Rabbitt, M. P., Reed-Jones, M., Hales, L. J., & Burke, M. P. (2024). Household food security in the United States in 2023 (Report No. ERR-337). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

35 Rabbitt, M. P., Reed-Jones, M., Hales, L. J., & Burke, M. P. (2024). Household food security in the United States in 2023 (Report No. ERR-337). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

36 Frazier, A. et al. (2023). Ch. 30: Hawai‘i and U.S.-affiliated Pacific islands. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 30-18.

37 Mankin, J.S., et al. (2021). NOAA Drought Task Force report on the 2020–2021 southwestern U.S. drought. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Drought Task Force; NOAA Modeling, Analysis, Predictions and Projections Programs; and National Integrated Drought Information System, p. 4.

38 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 401.

39 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 400.

40 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 407.

41 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 415.